Gittins Index Theorem and Multi-Armed Bandits

Zhiyu He, December 5, 2024

Adapted from

- Gittins, John, Kevin Glazebrook, and Richard Weber. Multi-armed bandit allocation indices. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Sébastie Bubeck and Nicolò Cesa-Bianchi. Regret Analysis of Stochastic and Nonstochastic Multi-armed Bandit Problems. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 2012.

Introduction

- Goal: solve sequential decision-making problems featuring exploration-exploitation trade-offs

- Salient feature: to find an optimal policy, it suffices to focus on an index corresponding to each choice and encompassing immediate rewards and future benefits

Motivating Example

- Two-armed bandit

Consider two slot machines that give the following reward sequences- Slot machine 1: $4, 5, 2, 6, 10, 1, \ldots$

- Slot machine 2: $8, 3, 10, 12, 1, 2, \ldots$

If not pulled, then the reward to be given is fixed.

How to sequentially select a machine (i.e., an arm) to maximize the discounted cumulative reward?

A myopic solution: $8 + 4a + 5a^2 + 3a^3 + 10a^4 + \ldots$

An arguably better solution $8 + 3a + 10a^2 + 12a^3 + 4a^4 + \ldots$

(For instance, if the discount factor is $a=0.9$, then the latter discounted sum is larger than the former) - Other examples

- Single machine scheduling

- Managing research projects

Three formulations of the bandit problem

- Criterion: the nature of the reward sequence

- stochastic (drawn from some unknown distribution)

-> upper confidence bound strategies

idea: construct upper confidence bound estimates on the means of arms and choose the arm that looks best under these estimates

principle: optimism in face of uncertainty - adversarial (arbitrarily set after we select the arm)

-> hedge algorithm

idea: maintain and iteratively update a probability distribution of selecting different arms - Markovian (features known state transition)

-> Gittins index

- stochastic (drawn from some unknown distribution)

-> upper confidence bound strategies

Problem Formulation

-

Simple family of alternative bandit processes

$n$ independent bandit processes $B_i, i=1,\ldots,N$ - two possible actions

- continue: produces reward and causes state transition

- freeze: no reward and the state is fixed

-

state $\xi_i$ lies in a countable state space $E_i$

-

At decision time $t$: apply control to a specific $B_i$

- Results

- obtain a reward $r_i(\xi_i)$ from the bandit process $B_i$

- the state of $B_i$ transits from $\xi_i$ to $y$ with probability $P_i(y|\xi_i)$

- other bandits are frozen: their states do not change, and no rewards are obtained

-

Goal: maximize the infinite-horizon expected discounted sum of rewards (i.e., the payoff)

\[\sup_{\pi} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} a^t r_{i_t} (\xi_{i_t} (t))\right]\]$a \in (0,1)$: discount factor $i_t$: the index of the bandit process chosen at time $t$

Why not alternative methods?

- Dynamic programming: the number of stationary policies (or the size of the state space) grows exponentially with the number of bandits

-

Value function

\[\quad V(\xi) = \sup_{\pi} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} a^t r_{i_t} (\xi_{i_t} (t)) \mathrel{\Big|} \xi(0) = \xi \right]\] -

Bellman’s equation

\[V(\xi) = \max_{i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}} \left\{ r_i(\xi_i) + a \sum_{y \in E_i} P_i(y|\xi_i)V(\xi_1, \ldots, \xi_{i-1}, y, \xi_{i+1}, \ldots, \xi_n) \right\}\]

number of states $\prod_i k_i \triangleq k$ for each state, we need to choose from $n$ actions

number of stationary policies: $k^n$

-

Gittins Index Theorem

-

Key idea: we aim to find an index indicating the behavior of a bandit process. This behavior blends immediate rewards and future benefits.

-

Point of attack: construct a simple reference bandit process

Calibrating bandit processes

-

Consider a discrete-time standard bandit process $\Lambda$, which gives a known reward $\lambda$ each time it is continued

If it is selected at every time, then the cumulative discounted reward is

\[\lambda(1+a+a^2+\ldots) = \frac{\lambda}{1-a}\]We want to compare a bandit process $B_i$ and $\Lambda$. Consider the following setting: we continuously apply control to $B_i$ and then follow an optimal policy.

This policy can switch to $\Lambda$ at some future time $\tau(\tau>0)$

-

Observation: if an optimal policy causes us to switch at time $\tau$, we will never switch back

-

Reason: the information on $B_i$ at time $\tau + 1$ is the same as at time $\tau$. If applying control to $\Lambda$ is optimal at time $\tau$, then it is also optimal at time $\tau + 1$ and afterwards.

The maximal payoff is

\[\sup_{\tau > 0} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t r_i(x_i(t)) + a^{\tau} \frac{\lambda}{1-a} \mathrel{\Big|} x_i(0) = x_i \right]\]We want to find $\lambda$ such that it is equally optimal to apply control to either of the two bandit processes initially, i.e.,

\[0 = \sup_{\tau > 0} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t r_i(x_i(t)) - (1 - a^{\tau}) \frac{\lambda}{1-a} \mathrel{\Big|} x_i(0) = x_i \right]\]We note that $\sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^\tau = \frac{1-a^\tau}{1-a}$. Therefore, $\lambda$ satisfies the following equation

\[0 = \sup_{\tau > 0} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} (a^t r_i(x_i(t)) - a^t \lambda) \mathrel{\Big|} x_i(0) = x_i \right]\]The right-hand side is the supremum of decreasing linear functions of $\lambda$. Hence, it is convex and decreasing in $\lambda$. The root exists and is unique. We obtain the following expression of $\lambda$

\[\lambda = \sup_{\tau > 0} \frac{\mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t r_i(x_i(t)) \right | x_i(0)=x_i ]}{\mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t | x_i(0)=x_i \right] }\]Another equivalent formulation

\[\sup\left\{\lambda : \sup_{\tau > 0} \mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t [r_i(x_i(t)) - \lambda] \mid x_i(0) = x_i \right] \geq 0\right\}\]Reason: the supremum $\lambda$ ensures that the expectation equals zero.

Interpretation of $\lambda$

- fixed reward that makes us indifferent to which of $B_i$ and $\Lambda$ to continue initially

- fair charge (highest rent) that we are willing to pay to continue $B_i$ for at least one round and then optimally switch

Observation

- with the supreme $\lambda$ and the optimal stopping time $\tau$, the cumulative discounted rewards collected from these bandit processes are the same

This $\lambda$ is the so-called Gittins index

-

Key statement

We maximize the expected discounted reward obtained from a simple family of alternative bandit processes by always continuing the bandit having greatest Gittins index. Namely, for

\[v(B_i, x_i) = \sup_{\tau > 0} \frac{\mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t r_i(x_i(t)) \right | x_i(0)=x_i ]}{\mathbb{E} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\tau-1} a^t | x_i(0)=x_i \right] }\]we always select the bandit process $i = \operatorname{argmax}_i v(B_i,x_i)$.

- Numerator: discounted reward up to $\tau$ (stopping time)

- Denominator: discounted time up to $\tau$

Note that the Gittins index only depends on the corresponding bandit process (or more specifically, $a, r_i, p_i$) but not on other processes.

Proof via prevailing charges arguments

-

High-level idea

(i) Construct an upper bound; (ii) show that this upper bound can be attained

Abstract example

Suppose that we have two functions $f,g$ such that $f(\pi) \leq g(\pi), \forall \pi$. If we find a policy $\pi^$ such that $f(\pi^) = g(\pi^)$ and $g(\pi) \leq g(\pi^), \forall \pi$, then $\pi^*$ maximizes $f(\pi)$ -

Prevailing charge $g_i(x_i)$: fixed charge that we pay to continue playing the bandit $i$ at state $x_i$

If $g_i(x_i)$ is too large, then we will quit playing this bandit -

Fair charge $\lambda_i(x_i)$: level of prevailing charge when we are indifferent at state $x_i$ between stopping and continuing for at least one more step and then optimally stopping

We give $\lambda_i$ in the previous ratio

Processes

- Initially, $g_{i,0} = \lambda_i(x_i(0))$

- A point will be reached when it would be optimal to stop continuing the bandit $i$. This point corresponds to the stopping time $\tau$. At this time, $\lambda_i(x_i(\tau)) < g_{i,0} = \lambda_i(x_i(0))$ This is also the first time that the prevailing charge is higher than the fair charge

- We reduce the prevailing charge and set $g_{i,\tau} = \lambda_i(x_i(\tau))$

- In general, $g_{i,t} = \min_{s\leq t} \lambda_i(x_i(s))$

$g_{i,t}$ is a nonincreasing function of $t$ and only depends on the states of bandit process $i$

Consider a simple family of $n$ alternative bandit processes $B_1, \ldots, B_n$. The gambler not only collects $r_{i_t}(x_{i_t}(t))$, but also pays the prevailing charge $g_{i_t,t}$ of the bandit $B_{i_t}$ chosen at time $t$. We have the following observations

-

The gambler cannot do better than break even (i.e., zero expected profit)

reason: a strictly positive profit is only possible if this were to happen for at least one bandit. However, we define the prevailing charge in a way (i.e., always equals the fair charge) such that no profit can be gained from any selected arm.Implications

\[\mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} a^t \left( r_{i_t}(x_{i_t}(t)) - g_{i_t}(x_{i_t}(t)) \right) \middle| x(0) \right] \leq 0,\]which implies that

\[\mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} a^t r_{i_t}(x_{i_t}(t) \middle| x(0) \right] \leq \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} a^t g_{i_t}(x_{i_t}(t)) \middle| x(0) \right]\] - We maximize the expected discounted sum of prevailing charges by always continuing the bandit with the greatest prevailing charge

Reason- Each sequence of prevailing charges is nonincreasing

- The above interleaving strategy maximizes the discounted sum

Example

- $g_1: 10, 10, 9, 5, 5, 3, \ldots$

- $g_2: 20, 15, 7, 4, 2, 2$

- optimal sequence: $20, 15, 10, 10, 9, 7, 5, 5, 4, 3, 2, 2$

Implication: the Gittins index policy $\pi^*$ maximizes the right-hand side

- The Gittins index policy $\pi^*$ of always continuing the bandit with the greatest index allows us to break even.

Reason: the Gittins index policy enables us to earn as much as those indicated by fair charges Note: if an arm is not pulled, then the state is fixed, and hence the corresponding Gittins index is unchanged.

Implication: the Gittins index policy attains equality

Alternative proof via interchanging bandit portions

- Intuition: let a bandit process with a higher reward run first

If in an optimal policy there is a point where we deviate from the arm with the greatest Gittins index, then by interchanging the order we can increase the reward. Hence, this contradiction implies that the optimal policy requires pulling the arm with a high index as early as possible.

Computational Example

-

Setup

We have $M$ independent bandit processes. Each process $i$ is endowed with a state $s_i$ belonging to a set $\mathcal{S} = {1, \ldots, N}$ and a known state transition matrix $P_i \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}$. At each state $s_i$, there is an associated reward $r_i \in \mathbb{R}$.At every time $k$, we will select a bandit process and receive a reward. The state of the selected process transits to a new value, whereas the states of the remaining processes keep fixed.

Our goal is to maximize the cumulative discounted rewards.

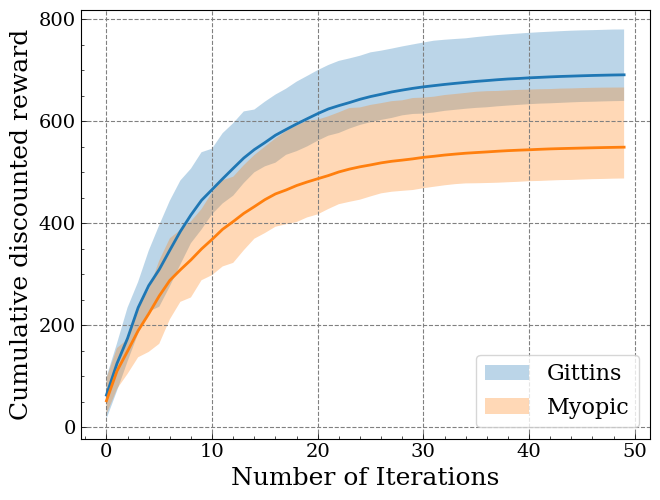

- Comparison

- Strategy based on selecting the maximum Gittins index

- Myopic strategy that selects the arm giving the maximum instantaneous reward

-

Codes

See the Colab link here - Results

The strategy based on the Gittins index yields a higher reward.

Summary & Extension

-

Summary

The Gittins index theorem provides an elegant characterization of the optimal policy for the multi-armed bandit problem with Markovian reward sequences. Instead of dealing with a vast Markov Decision Process, we only need to calculate the Gittins indexes of states of each arm and then obtain the optimal policy. -

Control

\[\begin{aligned} &x(t+1) = Ax(t) + Bu(t), \quad u(t) = -K_{i_t}x(t), \\ &\{K_i|i=1,\ldots,N\} : \mathrm{set~of~candidate~controllers} \end{aligned}\]

Setup: an unknown dynamical system and a set of candidate controllersChallenges

- dependent bandit processes

- the reward is not fixed if the corresponding bandit is left unchosen